Image Credits: Pixabay (Representational)

Many Realities About Hearing The Unspoken: Lost In Translation

India, 17 Jan 2023 9:39 AM GMT | Updated 17 Jan 2023 9:41 AM GMT

Creatives : Ankita Singh

A literature lover who likes delving deeper into a wide range of societal issues and expresses her opinions about the same. Keeps looking for best-read recommendations while enjoying her coffee and tea.

Much like mythologies, an entire body of performance and media narratives were being constructed as evidence to prove the already written theories. Although the ulterior motive of these being the ticket to gain relevance and validation in the world of dance for these writers, eventually feeding back into western academia for awards and promotions in their jobs was evident, it was becoming insufferable, particularly the tiresome inaccurate rhetorics.

Some years ago I started to become acutely aware of the dangers of post-colonial ethnographic scholarship in dance. Because, beyond remaining a personal project for the academic careers of the writers, such writings were beginning to be circulated as gospel truths.

Much like mythologies, an entire body of performance and media narratives were being constructed as evidence to prove the already written theories. Although the ulterior motive of these being the ticket to gain relevance and validation in the world of dance for these writers, eventually feeding back into western academia for awards and promotions in their jobs was evident, it was becoming insufferable, particularly the tiresome inaccurate rhetorics.

By controlling the narrative, claiming incomplete this or unfinished that...etc, sensationalism combined with "show and tell" story narrations of the life, history and performance of hereditary artistes, contrivedly stuck together by warped socio-political theories, borrowed out of context.

I wrote and spoke of this problem. The bigger concern, I felt, was not even these writers controlling the narrative, but a problem of these writers being completely ill-equipped to comprehend what they were encountering through short spans of ethnographic field work with hereditary artistes that they had, what then they were able to consume from these meetings, that too only in translation as they lack felicity in local languages, lack of depth to understand the nuances in socio cultural contexts which then reflected in their writing. What was said by the artiste, understood only via translation, then super imposed with borrowed theories that construe the past in a manner to make the present, a site of conflict.

Such tired populist rhetoric unfolded certainly in the case of Viralimalai Muthukannammal's narrative. A perfectly articulate woman, who can speak, dance and sing her life's work and experience, as witnessed by people who came to my event in 2020 and the more recent one that happened about which I write below. She was silenced and spoken about by the English language writing about her. As her student, I was privy to what she constantly says about her life. And I was sickened by the white washing and meshing of her narrative in ways that she had never consented to or worse till today cannot access or known enough to disagree with. Neither her, nor her next generations can do it, that is how far- off these projects are.

In 2020, having had enough, I organised a series called "GET REAL…" starting with Muthukannamal amma. For the first time, dancers, audiences and anyone who wanted to meet her were invited to speak to her directly. An un-mediated space via zoom (it was the pandemic time) made it possible for many dancers from across the globe to meet her as a living, breathing human, who can perfectly share her own story as opposed to having been reduced to a "subject" in an ethnographic exercise.

The zoom room reverberated with the voice of Muthukannamal amma. The whole evening was about asking her questions and she, answering them. This event was seen as a fresh approach to hearing their story in their voice, for the first time and people globally participated and loved it.

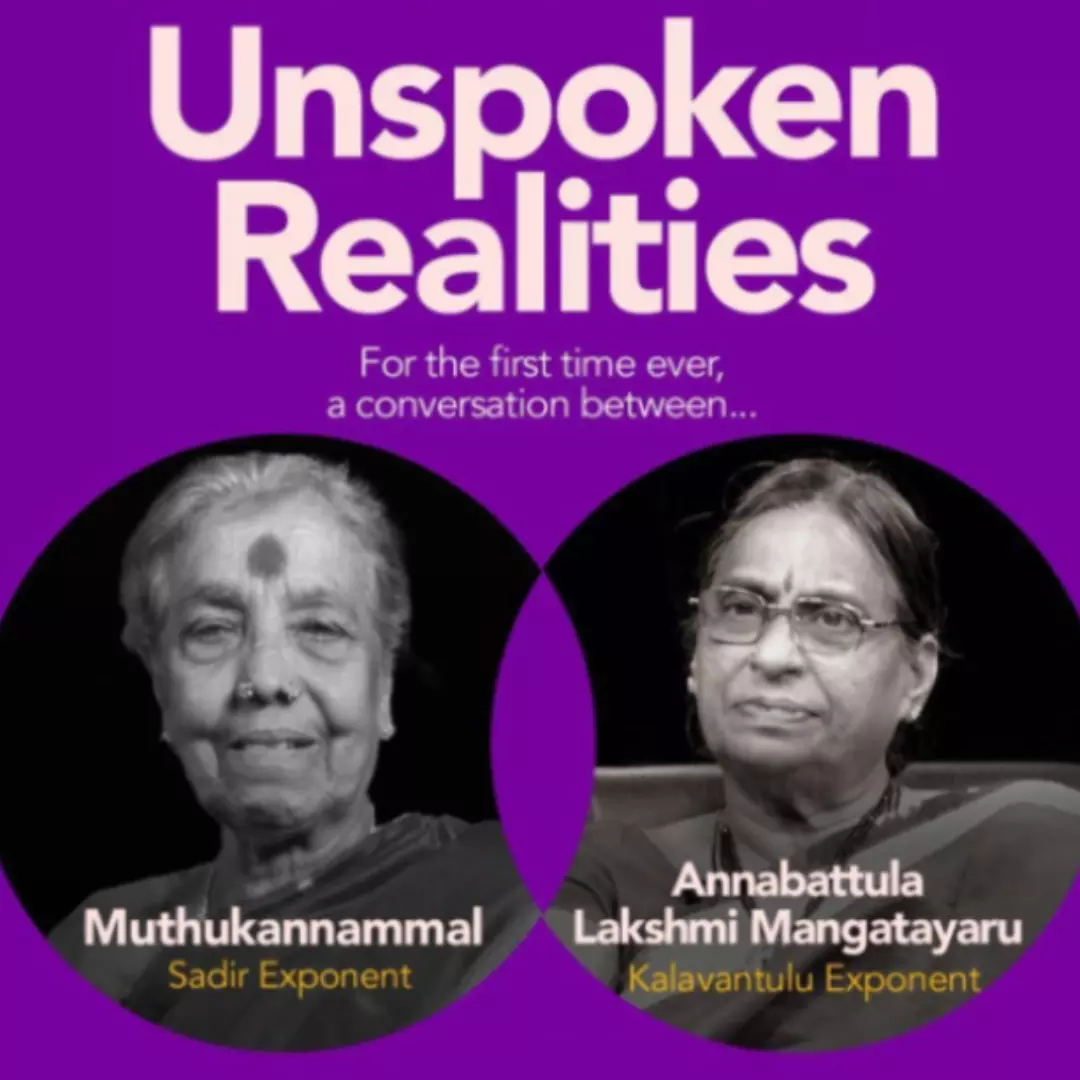

I am glad that more such efforts are being taken now. The recent event called "Unspoken Realities" organised by Shreya Nagarajan supported by senior dancer Malavika Sarukkai is commendable for bringing two voices - Annabatula Lakshmi Mangatayaru amma and Viralimalai Muthukannamal Amma on a stage to speak to the audience and between themselves.

However, it calls for reflections on the evening which for me, spoke many truths that were unspoken. Here are a few…

1. What are the take aways from such efforts? What does a dancer of Bharatanatyam, who has a thriving dancing career gain from knowing about the facts of how much land grants or food grains were given as part of the endowments to such hereditary families? What real use does that information have for them?

The knowledge of such past lived experiences of community artistes opens a window into the socio-cultural context from which dance and dancers have evolved over the years. Although today's context is a completely different one, to acknowledge and understand its economic, social nexus with people whose purpose of dance was livelihood and identity, is critical to know the distance we have travelled from it all, for example in terms of economic returns in the arts.

2. Apart from the fact that Annabatula amma and Muthukannamal amma are two celebrated artistes who have received recognition in recent years with SNA and Padmashree awards respectively, and that they are both from hereditary families, they share very little in common.

Throughout the evening, the two women spoke completely different languages. Not just literally, but significant was the stark contrast in their approach to their art and life as a Devadasi. While Annabatula amma's work revolved around more Sanskritic and Telugu literary references to repertoire, Muthukannamal amma spoke of her family's unbreakable bond to the temple and deity. Not in the divine sense (Bhakti as we understand today) but as a devotion to their service to the temple, as the epicentre of their artistry. Not much in her repertoire is outside this realm.

They didn't have much common articulations. Their worlds were complete in their own ways. They have no inquisitiveness to know, learn or share their experiences with each other or other similar women. When Annabattula amma asked out of a simple compulsion to ask a question to Muthukannamal Amma, "what kind of mudras do you practice in Sadir", she simply replied, we do anything that goes with the regular adavus and started to show "tattadavu". Similarly, when asked by Yashoda Thakore (herself a dancer who hails from a hereditary background, today a scholar as well), about "Padams and Javalis" in Muthukannamal's repertoire, she, with a nervous laughter asked, "what does she mean by javalis? I don't understand".

The evening did not have sensational moments of sisterhood. There was no shared moment of revelation. Two different women, varied practice, socio cultural scenarios, drawn together only by our will and in our minds as if they are two sides of the same coin. Much like writings where Kalavantulu women from Annabatula amma's family are chapter one and Viralimalai Muthukannammal amma was made chapter two.

3. So much was missed in translation right in front of our eyes.

While I credit Shreya and more importantly Yashoda for trying with great care to translate, this evening was a live demo of how much we miss in translation. The languages were only the first of the barriers. Yashoda speaks Telugu and English, Annabatula amma speaks only Telugu, Muthukannamal speaks only Tamil and most of the audience understand only English ! With rapid translations whispered into their ears, the two elderly women were distracted as much as they tried to grasp what was being said. But the more telling gaps in translation occur, when context is missed.

For example, when Yasodha posed a question to Muthukannamal amma about the impact of the 1947 act, the answer from amma was "It was not until Indira Gandhi abolished the privy purse that we actually faced any difficulty". A brief answer. The fact that the Privy purse abolition did not happen until 1971, the fact that despite being dedicated to the Viralimalai Murugan shrine her family was supported by the Pudukottai Palace and hence the effect of Privy purse is important to her, the fact that in spite of privy purse abolition, because Pudukottai Raja had a more cordial relationship with the then dispensation, many of the temples under his care thrived for a while longer than in other places and finally the fact that therefore the build-up of 1947 abolition of Devadasi dedication act, as a keystone moment across all devadasi- hereditary families in South India is a misnomer, were all lost on all those on stage as well as the audience. A critical difference in experience went unnoticed from plain sight.

I can go on quoting such misses, but what these proved ,is how much loss there is in translation, which then translated into English becomes not even a distant shadow of the truths that these women share.

4. Does the life and experience of Annabatula amma and Muthukannamal amma become the torch bearing truths of all or many of the hereditary families?

The fact that even within their own villages or towns there are and have been multiple, different practices and experiences. For example, Muthukannammal amma spoke of how they were asked to dance to a film song in a Sadir concert and how her father was reluctant. Annabatula amma said, "our dance is unlike cinema dance, purer and culturally valuable". These are their perspectives. But, contemporaneously we also know how many hereditary artistes readily plied to participate as actors, dance choreographers etc in early Telugu and Tamil cinema.

5. The inability of the secular to speak to the puranic/temple worlds

While it is to be agreed that Bhakti as a construct of "divinity" in a philosophical sense has overshadowed the erotic and sensual aspects of Sadir and Kalavantulu Natyam, which is its essence, Yasoda said she would rather prefer the term erotic than the term Srngara which she said is a Sanskritic understanding of the erotic. For a moment if we set the textual references aside, Srngara in fact, is the legitimation of the sensual and the erotic in all realms- human and deity within the lives of the hereditary artiste. The deity is humanized. The human was deified, in order to reconcile the emotions of love, lust and all things in between that are transactional in their many spaces.

Thanks to the academic separation of the puranic/ temple from the secular and progressive worlds through post-colonial writings, that generations of artistes suffer to see how women like Annabatula amma and Muthukannamal amma live and performed their Srngara within the temple premises without apology in commensuration of deity as the patron and the humanization of God.

6. So, if there are so many problems in translation, what are we to do?

The answer to all these above issues is not to undermine the importance and the need for un-mediated conversations between these kinds of artistes and the dancers. But, let us understand that there are no torch bearing hereditary -artiste -poster people. They are each different humans and artistes with varied cultural contexts. There exist no two similar stories or lived experience. Do not be misled by propaganda materials which pit such women, who don't even know of each other's existence, in pages one and two, as a running singular story, conflating their issues and lives in a present day agenda.

Let us acknowledge that as interested as we are in their lives, we are terribly ill-equipped to understand their language, unprepared and treat them really "from Mars-like" when we ask questions. Like the naïve dancer who posed the question from the audience at this event about Kshetrayya padams in Muthukannamal's repertoire, for which she looked completely puzzled, because she has never heard his name ! Even if she has performed a padam in Telugu that happens to be Kshetrayya, she would not be able to share such info in terms that we need it to be known. Like that NFDC documentary on Muthukannamal were, she was plucked from her own Murugan temple at Viralimalai, to which 7 generations of her family is in unbroken service, and planted in front of the Brihadeswara temple at Tanjavur to which she has never visited in her dancing years and went for only the second ever time during the shooting of this film! Just because the big temple is a more visually com

pelling background for the larger rhetoric, in a face-palm moment, the film comfortably white- washed her social context and blurred it with a popular "Tanjore as a seat of art" notion. And to this sad affair of marginalizing multiple places of art practice that are beyond the mainstream, comments from same such scholars who appear at their worst trying to pompously hand out righteous lessons on hereditary positions, gathered from their half-baked Tamil to English translations were added.

What sort of intellectual resources are you consuming? If not colonial in its very composition, the English language scholarship has muted many a subtle, nuanced and complex differences that make for many truths impossible to unfold in the discourse about the history of dance.

Finally, I was sitting next to Aniruddha Knight at this event. His great grand mother Veena Dhanammal amma was a celebrated hereditary artiste, as you might know. I wondered how much he related to what these two women were saying. I also imagined a stage set up to bring Late Dhanammal amma in conversation with Annabatula amma and Muthukannamal amma ! What a glittery, explosive, sensational event that would be. If that is what you are seeking.

Also Read: Leading The Way! Kozhikode To Enrol City's First-Ever Batch Of Student Cadets For Traffic Management

All section

All section